I'm frighten of the last stab

I'm frighten of the last stab

|

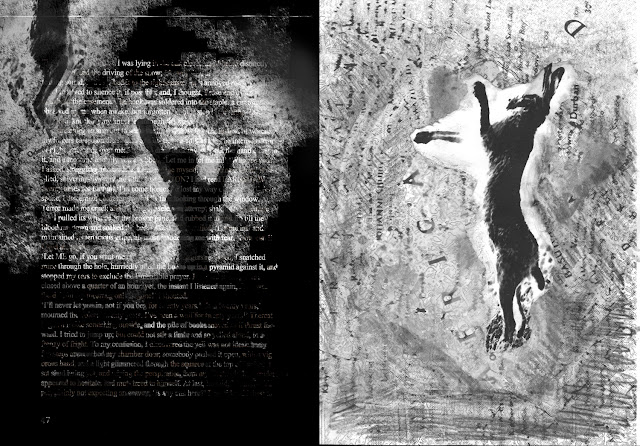

| Doppleganger |

|

| Hare & Magpie |

|

| Indecision |

|

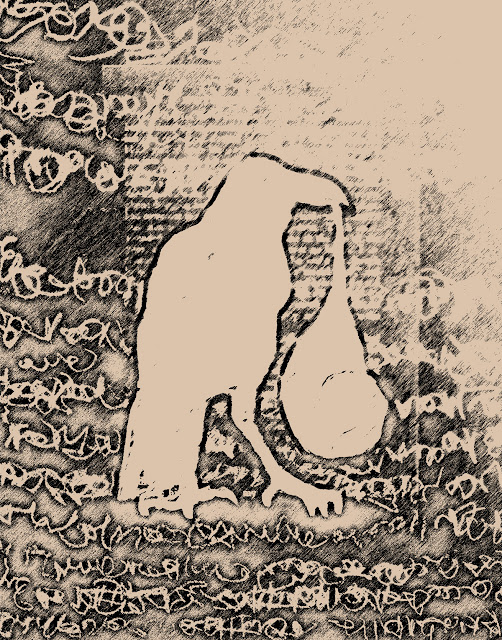

| Magpie & Bag |

|

| Hare |

Astoria

|

| STATHOPOULOU, VAFOPOULOUANTHOULA |

Twelve Reasons Why Ritsos

Wrote Scripture of the Blind Only for

Those Who See

I was born Zbigniew Jan Guzlowski in a refugee camp in Germany after the war. My father Jan Guzlowski loved that name Zbigniew. When he was a kid, there was a famous Polish wrestler who had a name like that, and my dad wanted me to have it. My mother was okay with the name too. Zbigniew was a common enough Polish first name, and she couldn’t see any harm in naming me that. Also, the roots of the name come from a couple of words in Polish that mean “to dispel anger.” After spending 3 years in a German slave labor camp, my mom was okay with dispelling some anger, I bet.

When we came to the US in 1951, however, we discovered something.

No one in the US could pronounce my name. Not only could they not pronounce my name, they had a great-old-time mispronouncing it. I was just a kid and other kids loved to make fun of my name. They called me big shoe and zigzag and bishop and zbubby and zuggy and on and on. They did this in the streets before I started school, and they did it in grade school even though I went to a predominately Polish grade school in Chicago. And they did it when I went to high school. Maybe it was even worst in high school. The guys there took to mocking my beautiful Polish name by mispronouncing it, and they accentuated the mocking by doing it in a high whining singing sort of falsetto.

I put up with this for 18 years.

When I finally became a citizen in 1968, I legally changed my name Zbigniew to John. Every American can say John. (Although most Americans still have trouble with Guzlowski–but that’s another story I’ll tell you some other time.)

But a funny thing happened to me when I got to be about 32 and started writing and publishing.

I decided not to use John Guzlowski or John Z. Guzlowski as the name my writing would appear under. Instead, I decided to write under the name Zbigniew Guzlowski. That’s right. Zbigniew Guzlowski.

I thought “Zbigniew” would catch the eye of any and every editor. You got to remember, this was the time in the late 1970s and early 19802 when Polish writers like Czeslaw Milosz and Tadeusz Różewicz and Wisława Szymborska and the great Zbigniew Herbert were getting a lot of press. I figured using “Zbigniew” would help me place some poems and stories and essays. You understand, I’m sure.

Maybe it would have happened, but I never got the chance to find out if re-attaching “Zbigniew” to “Guzlowski” would be the thing that helped me create a career for myself as a writer.

When my mom, a Polish immigrant, heard I wanted to use “Zbigniew,” she blew a fuse and said I couldn’t do it. I was 32 and she was telling me I couldn’t!

I was an American now, my mom said, and I had to have an American name.

Of course, like every good Polish boy, I listened to my mom.

ZBIGNIEW? by John Guzlowski was originally published via Dziennik Zwiazkowy. The original publication, in both Polish and English, can be read here.

Over a writing career that spans more than 40 years, John Guzlowski has amassed a significant body of published work in a wide range of genres: poetry, prose, literary criticism, reviews, fiction and nonfiction.

His poems and stories have appeared in such national journals as North American Review, Ontario Review, Rattle, Chattahoochee Review, Atlanta Review, Nimrod, Crab Orchard Review, Marge, Poetry East, Vocabula Review. He was the featured poet in the 2007 edition of Spoon River Poetry Review. Garrison Keillor read Guzlowski’s poem “What My Father Believed” on his program The Writers Almanac.

Lure

Black Widow Press, 2022

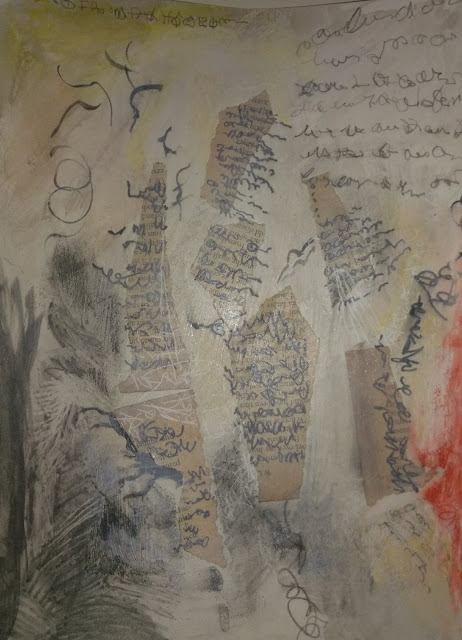

Imagine entering a loft

space, say in lower Manhattan, that is empty of furniture, but filled with a

number of randomly arranged objects: a car engine hanging from the ceiling on a

chain, a carrousel, a bunch of balloons, a stuffed coyote, a vase or orchids, a

cockatoo, a huge map of Budapest, a Civil War era cannon, a nude female mannequin

holding a polka-dot umbrella, and so on. How are these things related, other

than the space they occupy? There’s no immediate context that ties these

objects together. You might assume it’s an artist’s studio, but what kind of

art are they making? Everyone will have a different story. Everyone will weave

their own web of silky postulation. The creative urge will be aroused. And even

though there’s no answer or rational explanation for any of this, it’s still

intriguing. Something in you has been aroused. It gets the juices going. And

that’s what’s wonderful about collage. And this is the lure: the allure of the

lure is in its catalytic spark, the way it triggers a reaction in the

associative brilliance of the unconscious. Levinson’s Lure, as much of

his writing, operates on a similar principle.

There’s

always a feeling of space in Levinson’s writing, not just structurally or the

way the lines are arranged on the page, but psychologically, in the freedom it

offers. The openness of the language induces a state of uncertainty and

confusion, a little like being on a blind date. At first, you feel awkward. You

don’t know what to say. But if the date goes well, a random name or event might

pop up and break the ice and get the conversation going. Trying to find a

language to describe Levinson’s language is a challenge, partly because it runs

contrary to all the norms of modern linguistics, but also because there’s no

obvious message or mood, no evident narrative.

The

human mind is most at ease in a sentence with all its working parts in order,

riding along smoothly, guided by prepositions, connected by conjunctions,

hurled forward by predicates, with a well-upholstered syntax to lean into while

the various evocations, connotations, denotations, imputations and implications

provide a terrain upon which the mind can do its business. Thinking is hard.

Perception comes a little more easily, but it’s tricky. That’s why language was

invented. This worried Socrates, who believed that this luxury, when it became

written, would corrupt the mind with its hallucinatory power and erosive

convenience. He wasn’t wrong. That’s why reading has always struck me as a bit

decadent. The French symbolists took this to an extreme, creating an intricate

machinery of perfumed stars and pale naked bleeding wings out of nothing but

void and a glass of absinthe, a bit like the Federal reserve pumping money of

the air.

If

this sounds like conjuration, it is. Writing is essentially a magic act,

legerdemain, doves or endless scarves flying out of a sleeve or pocket,

voluptuous women sawed in two. Levinson takes us backstage to see how things

work, how the illusions are achieved. He’s a strange kind of magician. He wants

us to see that the real magic is in our own spirits, our own brains, our own

capacity to invent, to defy the constrictions – or constructions - of physical

reality.

The

writing is mostly asyntactic; prepositions, conjunctions, adverbs, and all the

other grammatical cogs and lubricants that orient our relationship to a

sentence are used with scrupulous spareness. Nouns proliferate. The effect is,

at first, a little jarring. You’re on your own. Torn down are the scaffolding

and pulleys of rhetoric. In its place are stacks of lumber and sacks of cement.

Where do you start? How are these things meant to be assembled? Not to worry.

The blueprint is already embedded in the brain, in the temporal lobe, just

behind the ear.

Take

“Gyration,” on page 62. “Gyration” begins with a quote from Edgar Allan Poe’s

Eureka: “We require something like a mental gyration on the heel. We need so

rapid a revolution of all things about the central point of sight, that, while

the minutiae vanish altogether even the more conspicuous objects become blended

into one.”

The

sense of urgency here and its proposed formula for experiencing the quantum,

non-linear universe surrounding us, is an appropriate lure.

The

first line reads: “seersight astral lyre fever kinetic threadout torque cycle

boost.” Wow. A lot to take in, I know. My immediate sensation is one of

teeming, words teeming, ideas teeming, substantives teeming, morphemes teeming,

everything teeming and streaming and gleaming and dreaming and beaming.

Sections of the line can be read variously as, “seersight astral lyre,” an

object I can picture so strongly a narrative emerges of a prophet and his

astral lyre playing the music of the spheres. Or: “lyre fever.” I’ll bet that

feels weird. Or: “kinetic threadout torque,” something that sounds a bit like a

software term, or aeronautical adventure. “cycle boost.” I know what that is:

that’s the thing you use to get your rocket into space when the gravity is

heavy, your boosters are pidgeonholed in semantic undergrowth and your pants

are down and the monsters are coming. That’s when you need a cycle boost.

And

this is just the first line.

The

next line reads: “pre-allocational fitness loop centripetal urge skin-in.”

Skin-in? What’s a skin-in? Is that anything like skinny-dipping? Prepuce? A

happening involving skin? Let’s get together and have a skin-in. I need a

skin-in. I don’t know what a skin-in is, I just know I need one.

Things

calm down a bit in the third line: “fringe hazard.” I know this one from

personal experience, and so give it a personal spin, a brisk gyration that will

send the minutiae spinning into space and the cosmic axis to bring us in closer

to the hub, the nucleus, the core, and away from the fringe, where the banners

are bananas and the hazards are hazardous.

And

so progress tends to be slow as I linger on these lines and let the words soak

in.

The

last line of “Gyration” is “Eureka.” Though actually it’s not, as the word is

split into “Eur” and “Eka,” which is how I read it, before I went “eureka!”

Eureka is, of course, the title of Poe’s book-length prose poem, as well as a sudden

triumphant discovery. Which is pretty much how I feel as I linger among the

lines in Levinson’s Lure, ingesting it slowly, so I don’t get too dizzy.